By C. van Tol

On the 10th of May 1940 the German army invaded the Netherlands. After five days of war, the capitulation was signed on 15 May 1940. Five difficult years of war followed, during which many crimes against humanity took place on Dutch soil. Fortunately, there were also countless acts of resistance.

After an attempt of the German armed forces to take possession of the Peace Palace was rebuffed by the impassioned pleadings of Dhr. Juliao Lopez Olivan[1], registrar of the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), the Peace Palace remained “neutral territory”.

During a visit of the Reichskommisar for the province South Holland in October 1943, it was announced that it was under consideration to house government departments in the Peace Palace. This led to protests by the board of directors of the Carnegie Foundation and fortunately did not come to pass.[2]

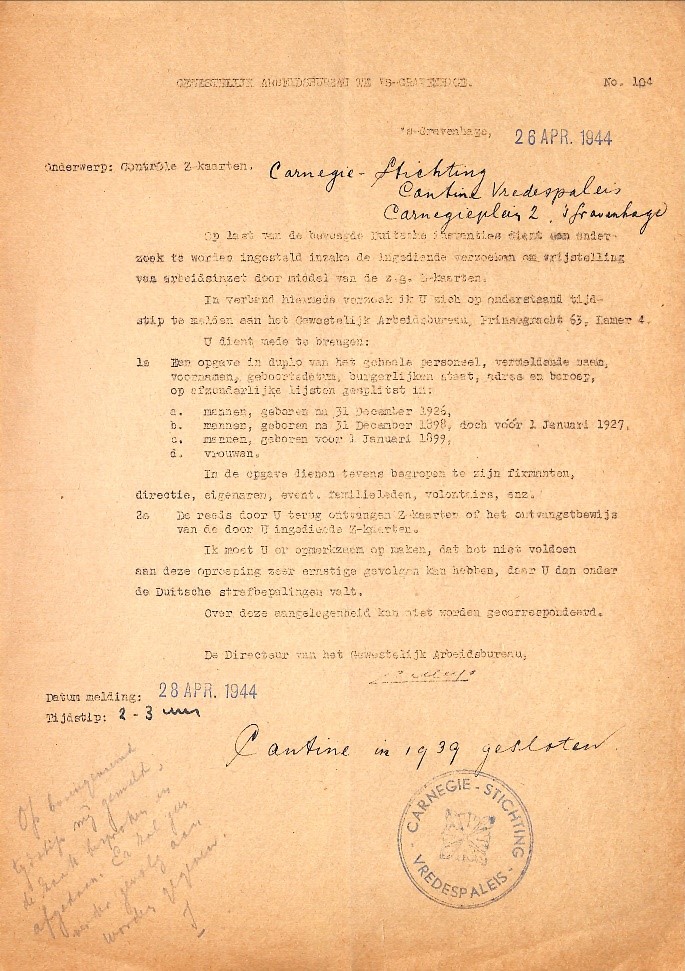

Call for check z-cards 26 April 1944

People in hiding, Refugees and Victims

The so-called Arian-declaration was a point of discussion among the board of directors of the Peace Palace. According to the board, two members of the staff risked being labelled Jewish. This was dangerous, therefore, it was decided to obstruct as much as possible and not to provide them with assistance. One of the two was the reading room assistant Ada Belinfante. Aside from her work for the Dutch government, Ada also collected books to enlarge the collection of the Peace Palace Library. Together with her brother Wim[3], she fled to England in May 1940. The identity of the second allegedly Jewish staff member remains unknown.

Another person at the Peace Palace who was at risk due to his Jewish heritage was Ernst van Raalte[4], in the spring of 1940 attached to the PCIJ as press attaché (probably an attempt to include him in the movement of the PCIJ to Switzerland) for whom Mr. Eysinga tried to arrange a trip to the United States through PCIJ Judge Manley O. Hudson[5]. Unfortunately, the attempt failed but luckily he survived the war in hiding.[6]

Among the staff members of the Carnegie Foundation there was a victim to be mourned; the 2nd conservator and librarian Theodor Max Chotzen. Called up for military service and having fought at the battle of the Grebbe-Line, this outstanding academic remained involved with the resistance during the war. In January 1945, Theodor and his family were arrested and incarcerated in the notorious prison at Scheveningen. Theodor was tortured in “Hotel Orange” and his wife and daughter were also maltreated. On 20 February, Theodor’s wife and daughter were released but on the 27 February, the body of Theodor Max Chotzen was deposited at the Municipal Disinfection Bureau[7]. Theodor’s wife and daughter got the body. The Carnegie Foundation donated an allowance to augment the pension of this unfortunate widow. [8] [9]

Theodor Max Chotzen in Uniform. Photographer unknown

Executive architect for the construction of the Peace Palace, J.A.G. van der Steur died in 1945 at Steenwijk “ ….after he had to endure the violence of war up close, on the 7th of February at Steenwijk, as the result of a fatal accident, unexpectedly passed away.”[10]

Another sad story was that of ex-employee Elsa Rachel Oppenheim. In 1916 she entered the service of the Peace Palace where she published an important catalogue of the collection in collaboration with Ph.J. Molhuysen, whom she married in 1920. Divorced in 1923, and from 1924 onwards working for the Leiden University Library, she was fired in November 1940 due to her Jewish background. Left without a means to make a living and under increasing threat from the occupation forces, she committed suicide on the 8 April 1941 in Leiden. She is buried in the Jewish cemetery of The Hague, close to the Peace Palace.[11]

Resistance and support

Through a number of employees, the Peace Palace was indirectly involved in the resistance. Besides Theodor Max Chotzen, Cock van Paaschen[12] was also active in the resistance. His mother was the head of housekeeping in the Peace Palace. And a young girl, Jos Gemmeke.[13]

Together these two printed the illegal paper “Je Maintiendrai” on the stencil machine of the Peace Palace. The machine was located in the basement but had to be moved to the attic every Friday, because there was a risk that the building’s keeper would hear it [14]. It is unclear if the board of directors or the other staff members knew about the use of the stencil machine.

After the PCIJ departed for Switzerland in July 1940, only the Dutch staff were left behind in The Hague to represent the interests of the court. The Carnegie Foundation continued its work in the war period and the library remained open to an increasing group of visitors. The fact that the reading room was heated could be part of the explanation.

During the war years, the library and Mr. Ter Meulen provided support to interned persons and refugees in a different manner; by delivering books. One of the people who received this aid was Mr. Karl Freudenberg[15], a German Jew with an interest in Hugo de Groot (Grotius). He had fled to the Netherlands in 1939 but was incarcerated in Camp Westerbork. Unfortunately, Mr. Ter Meulen had to halt this service in 1941.[16]

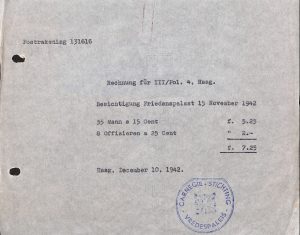

Guided tours to German soldiers

Guided tours are a part of the Peace Palace. During the Second World War this was already the case. During the war there have been a number of tours for German soldiers; “soldiers” were charged 15 cents while “officers” were charged 25 cents for these tours.

Tours were arranged through different organizations; the Bureau Vreemdelingenverkeer en Toerisme (Bureau Foreigners Traffic and Tourism) and the Departement van Volksvoorlichting en Kunsten, Afdeling Kulturele Propaganda (Department of Public Information and Arts, Section Cultural Propaganda).[17]

Damage, Devastation and Shortages

Bombings and the launching of the “Vergeltungswaffe” (retribution weapons, V-2 missiles) from The Hague left their marks in the city. The Peace Palace also did not weather the war without a scratch, although it was mostly limited to glass- and interior damage.

The bombing of the Rijksinspectie van de Bevolkingsregisters (Government Inspection of the Population Registers) in the Kleykamp Building on 11 April 1944, located just across the Peace Palace, was an expertly executed attack by the RAF. Although the targeted building was almost completely demolished, the Peace Palace remained in tact.[18]

Bombing of Kleykamp House, 11 April 1944. In the background the bell tower of the Peace Palace

As the war continued and local circumstances deteriorated, the garden was used to grow vegetables in order to alleviate the suffering, while a number of trees were sacrificed to meet the increasing need for fuel. Mr. Eysinga sometimes received from his Frisian family estate Boschoord shipments of potatoes and fire wood, which were generously handed out.[19]

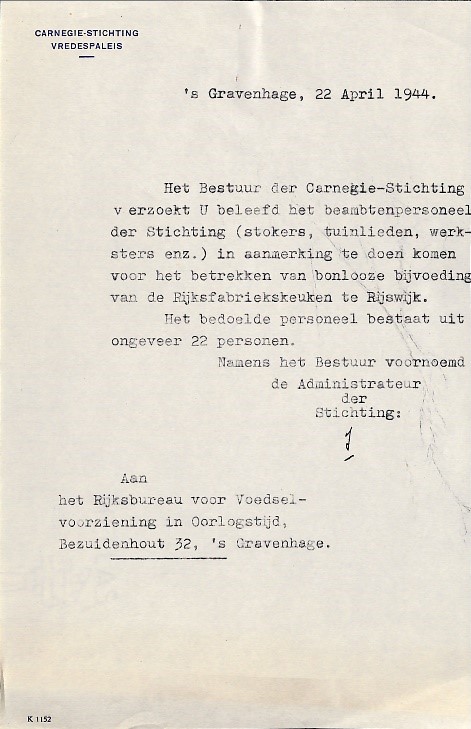

Letter requesting extra food assignments for the staff

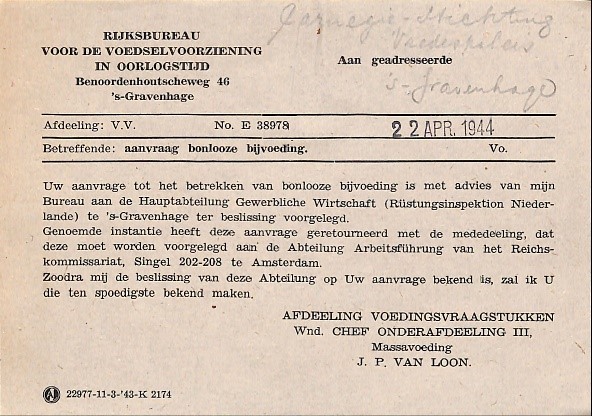

Reply providing an insight in the bureaucratic process

Liberation

After the liberation on 5 May 1945 it was possible to make up an overview of the damage. Although the Peace Palace had mostly weathered the war, the immaterial damage was extensive; lives had been lost and dreams were destroyed. Ms. Ada Belinfante immediately sent a message and after 1945 she returned to the Netherlands. The staff members who had been incarcerated in Germany returned home after the liberation.

The war was over and the reconstruction could begin.

This article will provide information on events in the surrounding area of the Peace Palace during the Second World War. A number of sources have been consulted to write this article. This is very much appreciated. Special thank you to Jacobine Wieringa for all aid and assistance.

Reference List

[1] Wikipedia Julio Lopez Olivan (Spanish)

[2] See letter Board of Directors Carnegie Foundation to F.L. Rambonnet. 7 October 1943. Dossier Rambonnet. Achives Carnegie Foundation..

[3] Joods Biografisch Woordenboek

[4] Parlement & Politiek – Ernst van Raalte

[5] Eysinga, Gestion des Affaires, I, pp. 15 en 16

[6] Nationaal Archief – Ernst van Raalte

[7] Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Stichting Oranjehotel: Doodenboeken, nummer toegang 2.19.136, inventarisnummer 174 Scan Nationaal Archief

[8] Dossier Chotzen. Archives Carnegie Foundation

[9] Een keltoloog, taalkundige en pacifist onder de wapenen en in het verzet.

[10] Verslag betreffende de bibliotheek van het Vredespaleis over het kalenderjaar 1945.

[11] Een zwarte bladzijde uit de geschiedenis van de UB Leiden

[12] Wikipedia – Cock van Paaschen

[14] De laatste Vrouwelijke Ridder. – Aanspraak. Maart 2009, p. 4-8

[15] Karl Freudenberg (1892-1966) Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. 2011, p. 439

[16] Bouwen aan Vrede : Honderd haar werken aan Vrede door Recht. 2013, p. 131

[17] See Dossier Rondleiding Duitsche Militairen 1940-1945. Archives Carnegie Foundation